Mould may have a reputation for turning the cleanest home and most prized possessions into damp, disintegrating relics but when left unchecked, certain moulds can have the same effect on our health, writes medical researcher and female health advocate, Dr. Emily Handley.

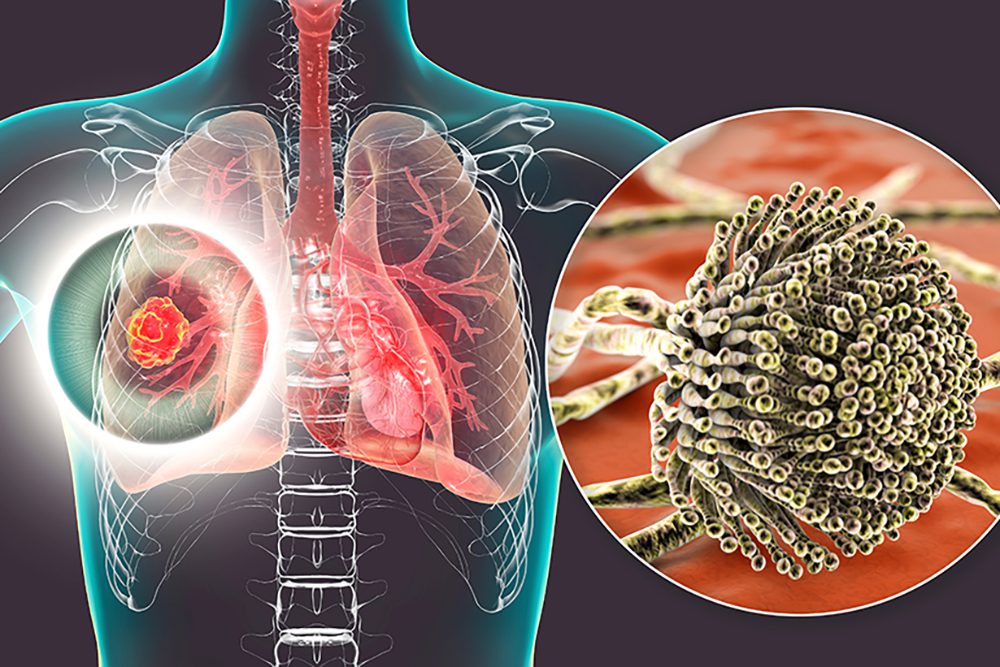

Mould: it’s the microscopic fungi that can be found essentially everywhere, living on plant or animal matter and spreading by floating through the air. Normally, mould is just a component of our everyday environment, and has critical roles in breaking down organic matter.

When mould spores land on a wet or a damp spot in the home, they form colonies that digest organic matter – leading to damage of buildings and belongings. When left unchecked, certain forms of mould can also pose serious health problems, particularly for those with allergies, respiratory conditions or a weakened immune system. The most serious issues are caused by mycotoxins, produced by mould when threatened; much like an octopus or squid squirts ink.

Types of toxic mould

There are thousands of different types of mould, and the vast majority pose no serious threat to our health. Yet some species can induce health issues, and it is vital to recognise these moulds and know potential impacts. Typically, moulds fall into categories of allergenic or toxigenic, covering different sets of symptoms.

- Acremonium: a toxigenic mould that is initially a small, damp spot that becomes a fine powdery substance. Often grey, orange, white or pink in colour; grows in household systems such as cooling coils, window sealant and humidifiers.

- Alternaria: allergenic mould and grows in excessive dampness – baths, showers and at leaking sinks. A textured mould with dark green or brown hairs, associated with water damage to the home.

- Aspergillus: allergenic mould forming flask-shaped spores that becomes thick layers. Over 185 species, and toxicity depends on the environment affected and species present.

- Aureobasidium: found behind wallpaper, painted or wooden surfaces. An allergenic mould, it develops a pink, brown or black colour, becoming darker brown with age.

- Chaetomium: found in water-damaged buildings and homes; damp roofs, sinks or cellars, and creates a musty odour. Has a cotton-like texture, and changes colour over time from white, to grey, to brown and finally to black.

- Cladosporium: can grow in warm and cold conditions, thriving in materials such as upholsteries, fabrics, carpets, inside cupboards and under floorboards. It presents as an olive-green or brown colour, with a suede texture.

- Fusarium: capable of growing and spreading at cooler temperatures. Both allergenic and toxigenic; grows following water damage in carpeting, wallpaper and other materials and fabrics. Pink, white or reddish in colour and grows on food products.

- Mucor: grows in thick patches, near air conditioning due to moisture from condensation. Allergenic mould and white or grey colour with a fur-like texture; can also be found in old, damp carpets.

- Penicillin: allergenic mould with blue-green surface and velvet in texture. Found in water damaged buildings, and in carpets, wallpapers and mattresses.

- Trichoderma: grows in white and green patches, with a woolly texture that becomes more compact. An allergenic, found on wet surfaces and on wallpaper, carpet and damp fabrics.

- Ulocladium: located in kitchens, bathrooms, cellar and around windows with consistently high condensation levels. It is typically black in colour and indicates water damage.

- Stachybotrys: toxigenic mould form, can also cause allergic reactions and lives in damp, wet areas with high humidity. Dark green or black, with a slimy texture; grows on cellulose material such as wood, paper, hay, wicker or cardboard.

What are mycotoxins?

The most serious health problems linked to mould are caused by mycotoxins: small molecules released by mould when colonies feel threatened. Mycotoxins are made by fungi and moulds and are toxic in low concentrations; but they are hard to define and classify due to vast diversity and different biological effects. Additionally, the quality of scientific research into mycotoxicosis, the diseases caused by mycotoxins, is incredibly variable, with a high amount of inaccuracy, false information, and theories that were long ago disproven – yet continue to be considered fact.

For some forms of mycotoxins, low levels do not cause issues for individuals and can even be found in low amounts in food. However, some forms are toxic even in small quantities; these range from annoying – such as foot fungal conditions – to life-threatening. How mycotoxin poisoning presents itself can depend on type of mycotoxin; amount; duration of poisoning; age; sex; health status; diet and genetics, among other factors, creating a range of outcomes. Mycotoxins can cause damage primarily via our airways or through ingestion of certain foods, and can worsen vulnerability to other microbial diseases, effects of poor nutrition and that of other toxins.

What are the symptoms of mould allergies or toxicity?

Like many toxic-induced syndromes, mycotoxicosis can be acute or chronic. Acute occurs rapidly, with a clear toxic response, while chronic exposure occurs over time can induce cancers, immune suppression and kidney toxicity, amongst other long-term health impacts. Mycotoxicity falls into two categories: immune reactions and chemical/inflammatory reactions. Immune reactions are most common, presenting as allergy-like symptoms, and can include sinus issues; runny nose; itchy skin and eyes; shortness of breath; and asthma. Mycotoxins can create a histamine response that can be relieved by antihistamines, but this may also become a more serious allergy that needs to be checked with a blood test.

A chemical mycotoxin response occurs after the molecules induce a cytokine-response – also known as a chronic inflammatory response. The symptoms of this condition can vary and follow no known pattern, as well as occurring across a range of other diseases. This response can be misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis; psychosis; food or insect allergies; migraines; and chronic fatigue syndrome. Symptoms can be mental: such as brain fog; poor memory and concentration; anxiety and mood changes; or physical, such as weight gain or loss; fatigue; dehydration; digestive issues; tinnitus; hair loss; dermatitis; and dizziness.

People most at risk of these symptoms associated with mycotoxicosis are infants and children; the elderly; those with respiratory conditions or allergies; and people who already have a weakened immune system, either due to medication or a chronic condition. If you feel that you fall into one of these categories and experience these symptoms associated with the presence of mould, see a doctor immediately.

Table 1. Most common mycotoxins

| NAME | WHAT IS IT? | HEALTH IMPACTS |

| Aflatoxins | Produced by Aspergillus moulds. Found in crops and milk products. | Toxic and carcinogenic; acute exposure can cause death and chronic can cause cancers, liver damage and immune suppression. |

| Citrinin | Found in Penicillium and Aspergillus. Present in rice, coloured vegetarian foods, fermented sausage and grains. | Impacts kidneys, and has acute toxicity. Most research from animals, with no clear findings for human health yet. |

| Ergot alkaloids | Found in Claviceps, a pathogen of grass species. Ingestion has caused disease since antiquity; also known as St. Anthony’s fire; common in Europe in the Middle Ages. | Can be gangrenous and convulsive. Gangrenous affects blood supply to extremities; convulsive impacts nervous system. Described as a slow, nervous fever. |

| Fumonisins | First found in 1988; member of Fusarium moulds. Can cause rotting and corruption of crops. | Can have severe impacts on the liver; induces cancer, particularly of the oesophagus. |

| Ochratoxin | Produced by Aspergillus; grows on different materials exposed to warm, damp conditions. Found in grains, particularly barley, and pork. | Primarily targets the kidneys; potentially involved in chronic nephritis and urinary tract tumours in Balkan states. |

| Patulin | Excreted by Penicillin; Found in unfermented apple juice. | Known to be toxic at high concentrations, but evidence for natural poisoning from exposure is still inconclusive. |

| Trichothecenes | Produced by Fusarium, Myrothecium, Phomopsis, Stachybotrys, Trichoderma, Trichothecium and others. Found as food contaminants. | Can cause haemorrhaging, vomiting, and dermatitis after ingestion and direct contact; also has immune suppressive effects. |

How is myotoxicity diagnosed?

The number of people affected by mycotoxicosis is still unknown due to the difficulty in recognising symptoms and clear diagnoses – though we do know that it is more prevalent in under-developed countries and is not a contagious disease. Yet even in more developed countries, consuming certain grain products that do not meet safety standards, and living in buildings with high mould levels increases the risk of developing a toxic response to mycotoxins. Diagnosis of mycotoxicosis requires evidence of a dose-and-response relationship: a clear connection between mould or mycotoxin exposure and symptoms. This can be validated with environmental monitoring, such as measuring mycotoxins in a person’s food, the air in their home and the presence of different substances on their clothing and possessions.

If you are aware of extensive mould in the home and present with one of or a combination of the symptoms above, seek medical advice immediately.

Most commonly, mycotoxins are detected via urine testing; yet this can be misleading, as it is only measuring the amount of mycotoxin the body can process and excrete. Blood tests are also available but are not always able to detect true levels of mycotoxins present. It’s important to keep in mind that we currently have no efficacious diagnostic tools for mycotoxicosis commercially available, and the results from tests on the market at the moment are often not medically valid. Currently, researchers are trialling laboratory testing in grains to optimise the validity and speed of diagnosis. These are based on current methods already used in research, and may prove highly suitable for finding out the level of mycotoxin a person is exposed to, and further reading on these can be found here.

How is mycotoxin-induced illness treated?

Aside from supportive therapies and pain relief – such as dietary changes, hydration, anti-inflammatories, physiotherapy etc – there are almost no treatments for mycotoxin exposure. Though not all hope is lost; we do already have some veterinary treatments that may one day be optimised for humans, and there are ongoing drug trials for diseases linked to mycotoxins.

If you are experiencing any of the symptoms mentioned here, it doesn’t matter whether they may be mould related or not – see your general practitioner immediately, as they can be signs of many other serious diseases and conditions. After speaking to a medical professional, if you do notice an association between symptoms and the presence of a toxic mould species in your environment it is important to rule out non-mycotoxin-causes of illness. To do so, try leaving your environment for 1-2 weeks, and seek the advice of a mould-removal specialist.

To remove mould from the home yourself, determine the type of mould, what materials are affected and ensure you have the appropriate protective equipment. Hard, non-porous surfaces can be treated with bleach, whilst porous materials need specific solutions – or professional removal. Extensive mould growth, or severe water damage in a building can create irreversible damage to your home, and evidence of this almost always requires professional assessment.

Mould and mycotoxins love damp and humid environments, so the best way to prevent growth is to monitor humidity in the home. The devices available for this have varying reliability; humidifiers are a more consistent way of controlling humidity in your environment. Regularly cleaning bathrooms and other wet areas, as well as ventilating the home often can also prove effective against a mould infestation. Additionally, mould-inhibiting paints can be used to stop growth on walls and ceilings. Finally, avoid carpet or other porous materials in the kitchen and bathroom, and dispose of any water damaged materials.

So, what is the bottom line?

While mycotoxins have been implicated in a range of disease outbreaks across human history, it can still be incredibly difficult to link adverse health to mycotoxicosis. Most health problems are more readily linked to inhalation of mould spores themselves, as well as contaminated dust in buildings. However, this does not discount these tiny products from being causal in many diseases. Occupants of water damaged, and air-conditioned buildings still report a range of adverse health effects, and exposure to moulds and fungi undoubtedly has negative impacts. Due to the difficulty in diagnosing mycotoxicosis, the best way to determine the cause of illness is to take yourself away from your normal environment and keep a record of the symptoms you experience over time. Maintain appointments with your doctor and prevent mould build-up in the home for the best prevention.

In lieu of conclusive research and diagnostics, the best treatment for mycotoxin and mould-related disease is knowledge and prevention.

Disclaimer: This article provides general information only, and does not constitute health or medical advice. If you have any concerns regarding your health, seek immediate medical attention.